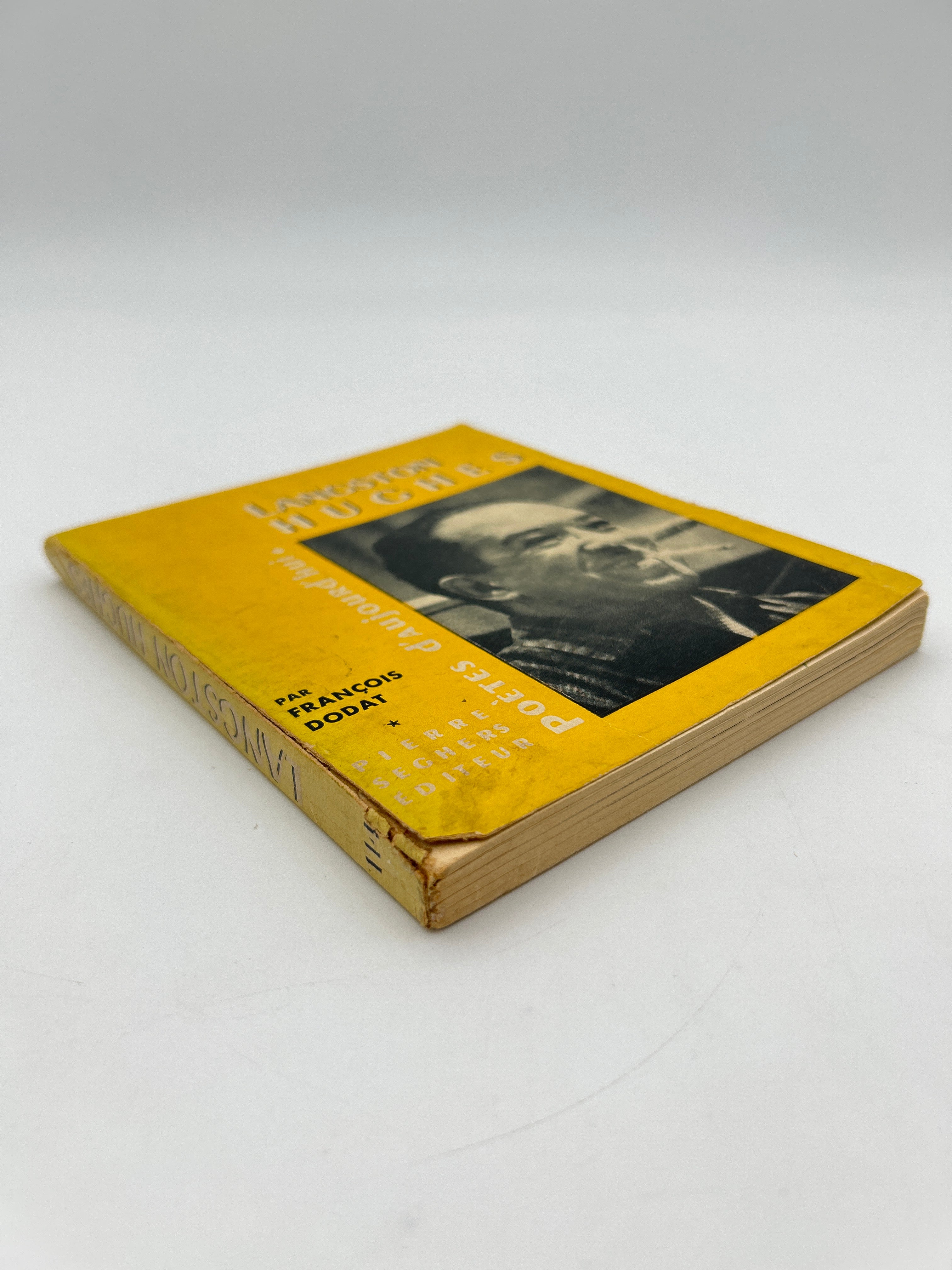

Langston Hughes

Couldn't load pickup availability

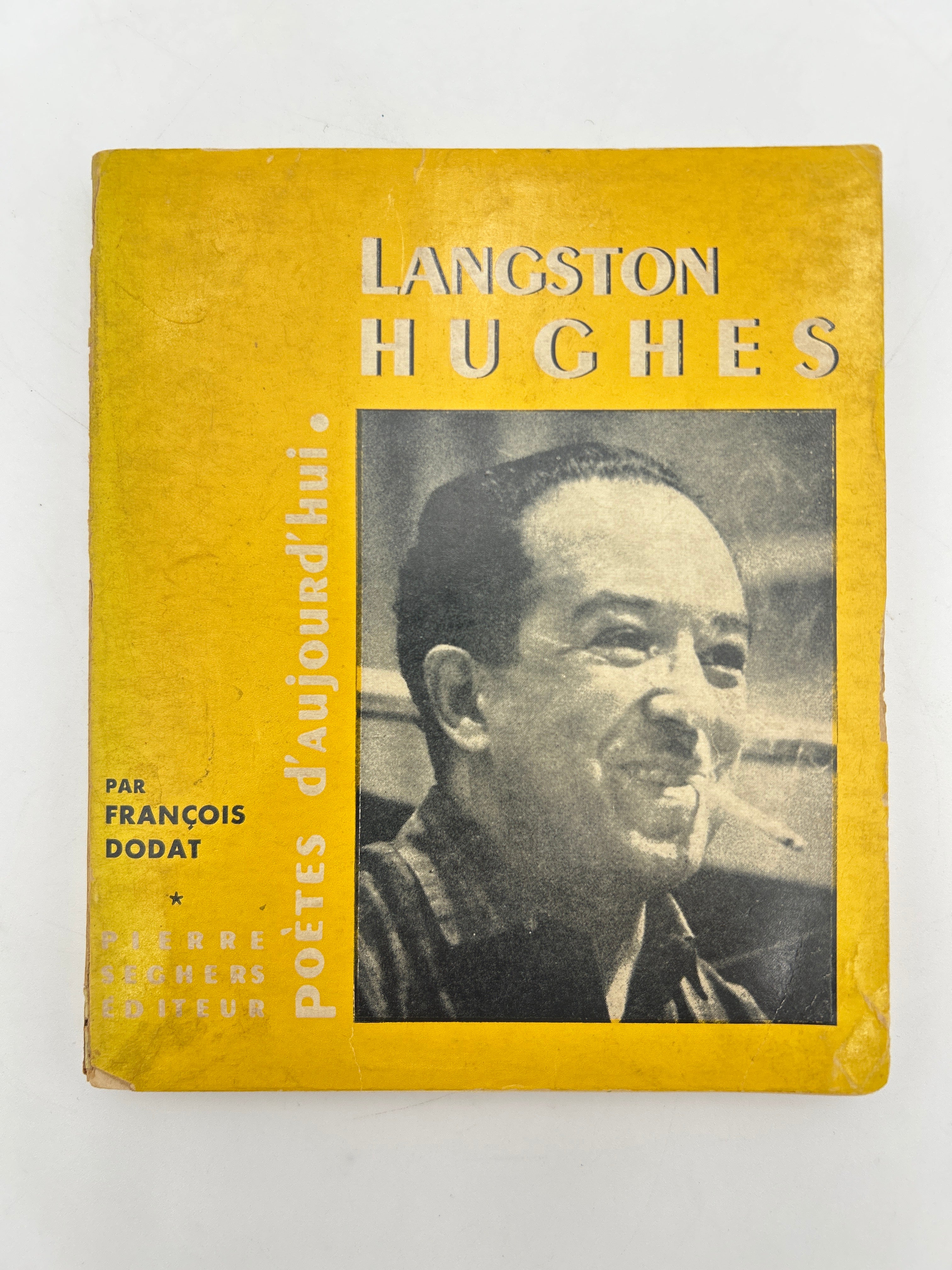

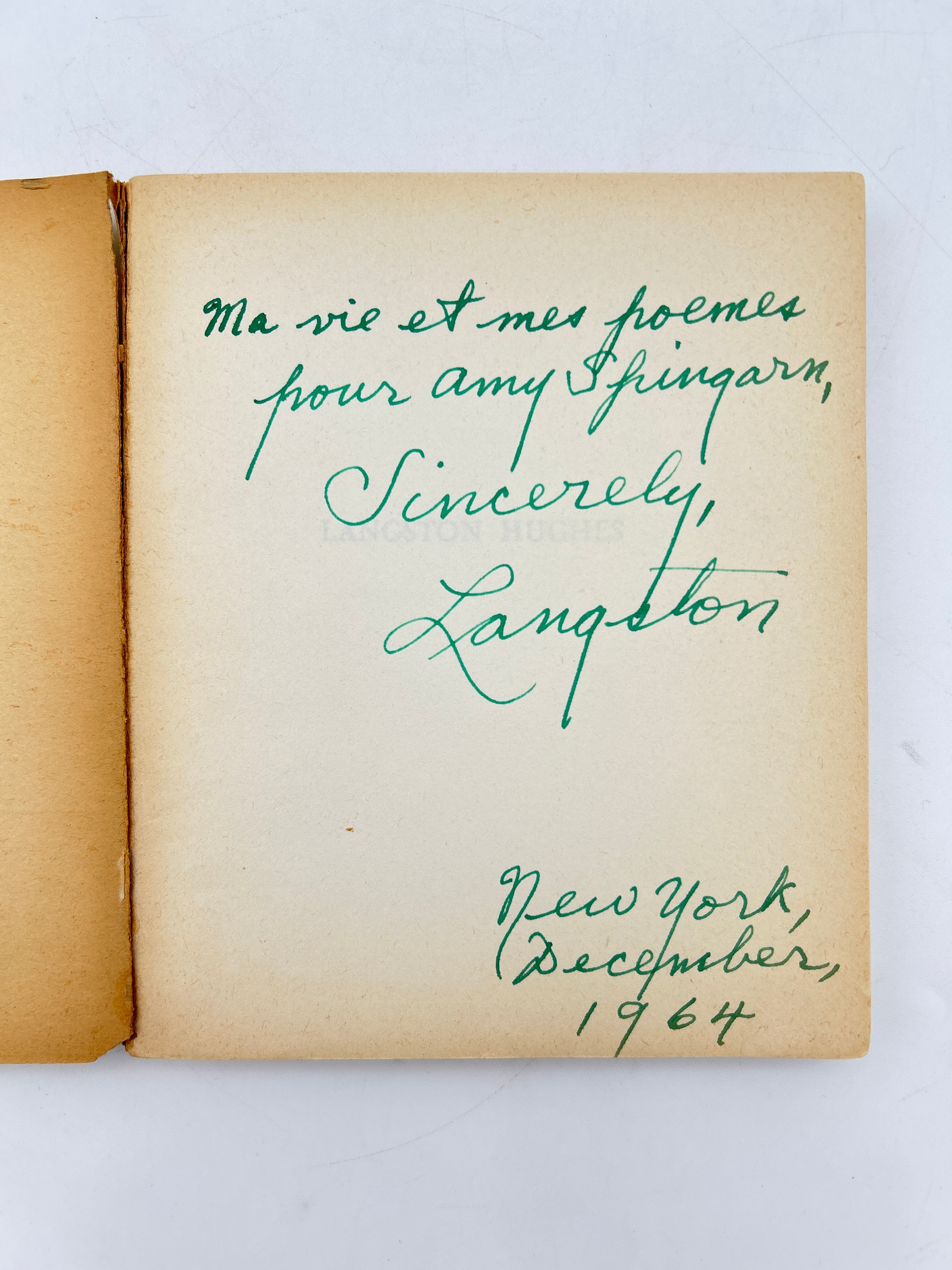

5b Francois Dodat. Paris, 1964. in French. INSCRIBED by LANGSTON HUGHES

Notes

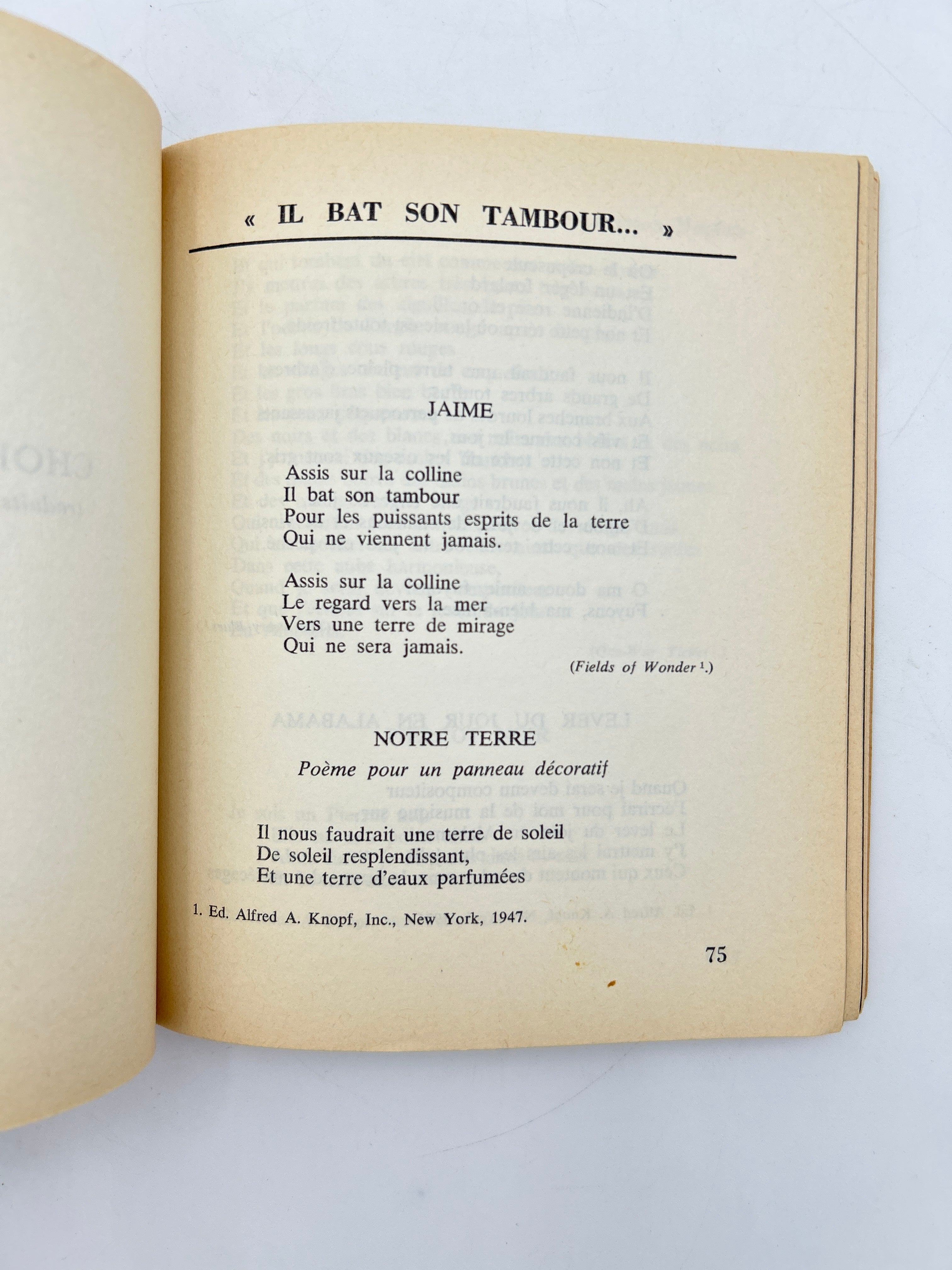

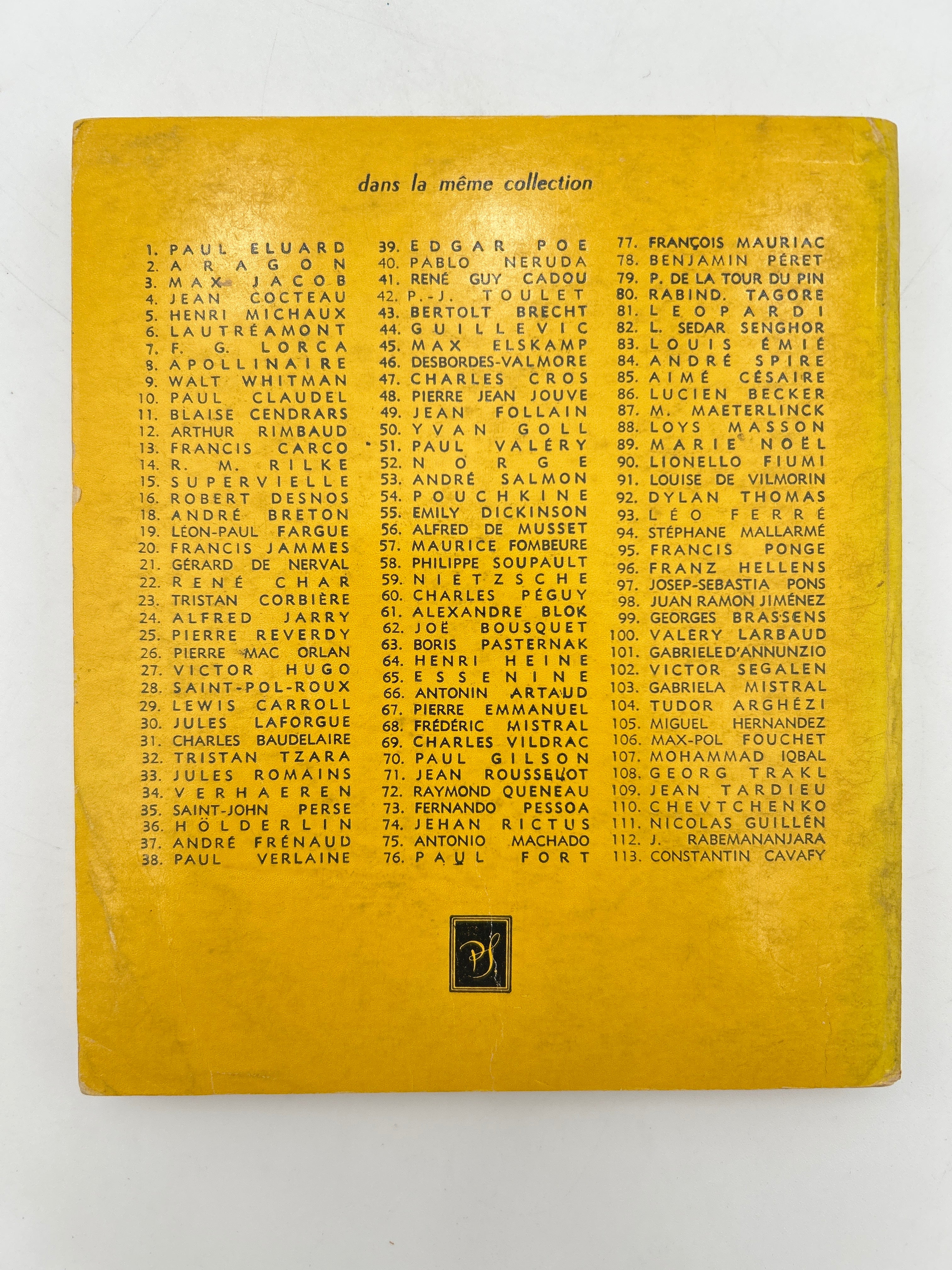

Langston Hughes by François Dodat (1964) is a French critical monograph published as part of the well-known “Poètes d’Aujourd’hui” series by Éditions Seghers, which introduced major international poets to a French-reading audience. In this volume, Dodat presents Hughes not only as a central figure of the Harlem Renaissance but also as a politically engaged writer whose poetry, prose, and theatrical works captured the rhythms, struggles, and aspirations of Black American life. The book combines biography, critical interpretation, translated excerpts of Hughes’s poems, and commentary on his stylistic innovations—especially his use of jazz, blues, and colloquial speech. Designed in the characteristic Seghers style, it offers a compact yet authoritative portrait of Hughes’s cultural significance at a time when European interest in African-American literature was rapidly expanding.

Langston Hughes (1902–1967) was one of the most influential voices of the Harlem Renaissance and a defining figure in 20th-century American literature, celebrated for bringing the cadences of jazz, blues, and everyday Black speech into poetry with unprecedented power. As a poet, playwright, novelist, essayist, and social commentator, Hughes chronicled the joys, frustrations, resilience, and cultural brilliance of African-American life with clarity, empathy, and artistic innovation. His works—ranging from The Weary Blues and Montage of a Dream Deferred to his popular “Simple” stories—challenged racial stereotypes, elevated Black cultural expression, and foregrounded the importance of social equality and artistic freedom. Hughes’s significance to history lies not only in his literary achievements but in his role as a cultural bridge: he helped solidify African-American artistic identity on the world stage and inspired generations of writers, musicians, and activists during the civil rights era and beyond.

Langston Hughes’s connection to Amy Spingarn was rooted in friendship, artistic support, and a long-running correspondence that reflected her genuine encouragement of his work. Amy, the wife of NAACP leader and literary patron Joel Elias Spingarn, was herself an artist and an early admirer of Hughes’s poetry; she reached out to him in the 1920s, and the two developed a warm, respectful relationship that lasted for decades. She purchased his books, offered emotional encouragement during difficult financial periods, and maintained an ongoing exchange of letters that showed her deep interest in his creative life and personal well-being. Hughes, in turn, trusted her as a sympathetic reader and valued the stability and generosity the Spingarns extended to him and many other young Black writers of the Harlem Renaissance. Their relationship stands as an example of the quiet but meaningful patronage networks that helped sustain emerging African-American artists in the early 20th century.

Hughes also maintained a long and meaningful relationship with France, beginning in the early 1920s when he lived in Paris, worked odd jobs—including as a busboy and shiphand—and immersed himself in the city’s vibrant Black expatriate and jazz communities. He admired French culture, became conversant in French, and found in Paris a level of artistic openness and racial acceptance he often felt was denied him in the United States. French writers, critics, and publishers embraced his work early; his poetry was translated into French during his lifetime, and he was well respected among French intellectuals, leading to studies such as François Dodat’s Poètes d’Aujourd’hui volume. This reciprocal relationship helped broaden Hughes’s international reputation and reinforced his role as a cultural ambassador of African-American art and identity.

Description

Yellow softcover in original wrapper. Front cover beginning to split from back strip at bottom. Inscribed in green ink by Hughes to Amy Spingarn; “Ma vie et mes poemes pour Amy Spingarn, Sincerely, Langston, New York, December, 1964” French text.