Latin Vulgate Bible 1492

6B, Holy Bible in Latin. known as Columbus Bible with first version of title page. 1492

Notes

The Columbus Bible of 1492, also known as the "Biblia de Cristóbal Colón," is a significant artifact associated with Christopher Columbus. This edition of the Bible, printed in Latin, was carried by Columbus on his historic voyage to the Americas in 1492. It symbolizes the intertwining of religious faith and exploration during the Age of Discovery. The Columbus Bible reflects the era's broader cultural and intellectual currents, serving as a spiritual guide for Columbus and his crew as they embarked on their groundbreaking journey across the Atlantic Ocean.

Before the invention of the printing press, handwritten Bibles were painstakingly copied by monks and scribes, often in monasteries or scriptoria. These manuscripts, typically written on parchment or vellum, could take years to complete. Many were illuminated with gold leaf and intricate illustrations, especially in deluxe versions used for display or ceremonial purposes. Latin was the dominant language for these texts in medieval Europe, and due to the immense labor involved, owning a Bible was rare and often limited to the Church or wealthy individuals. Each copy was unique, with regional variations in spelling, decoration, and marginal notes.

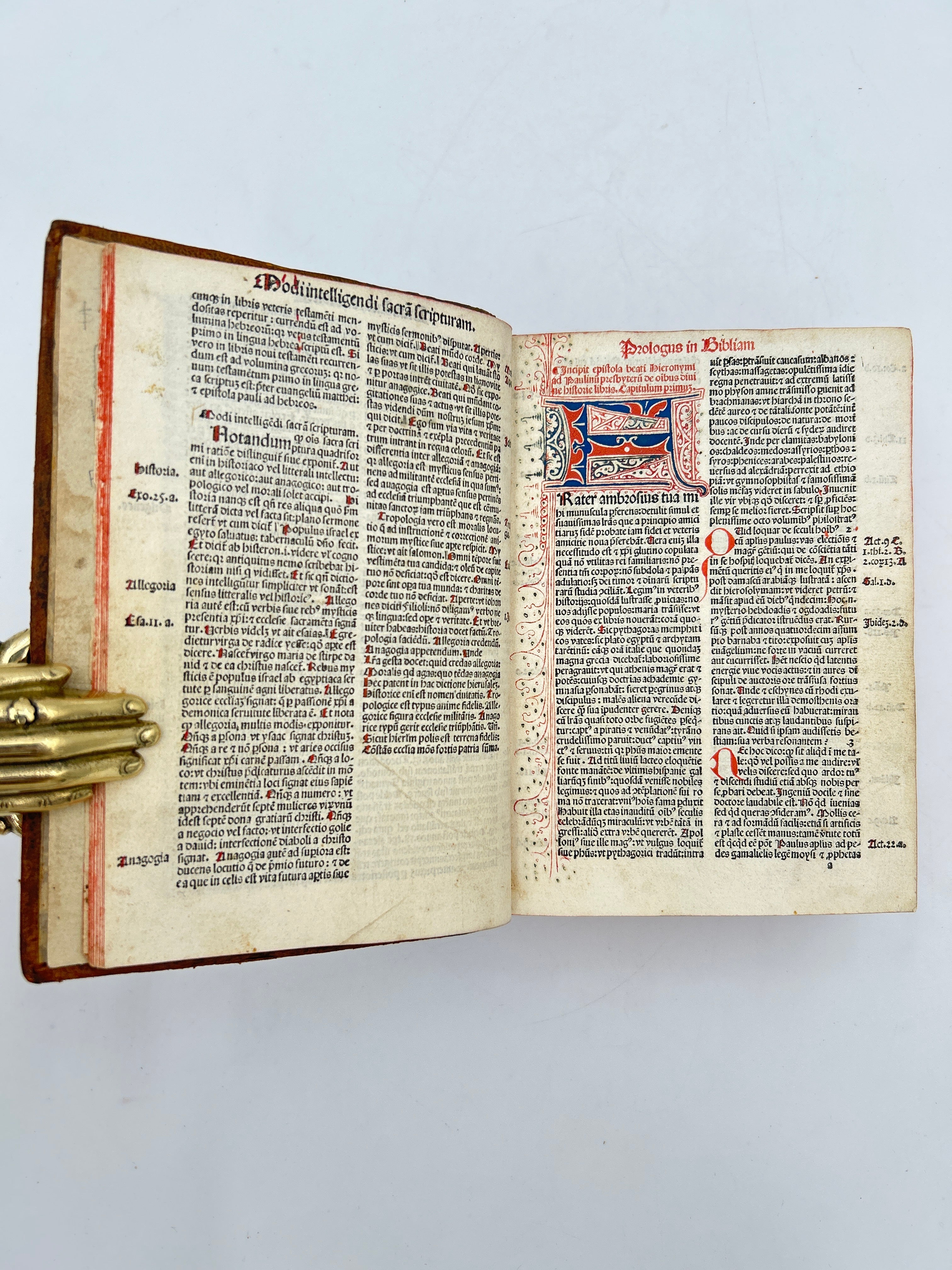

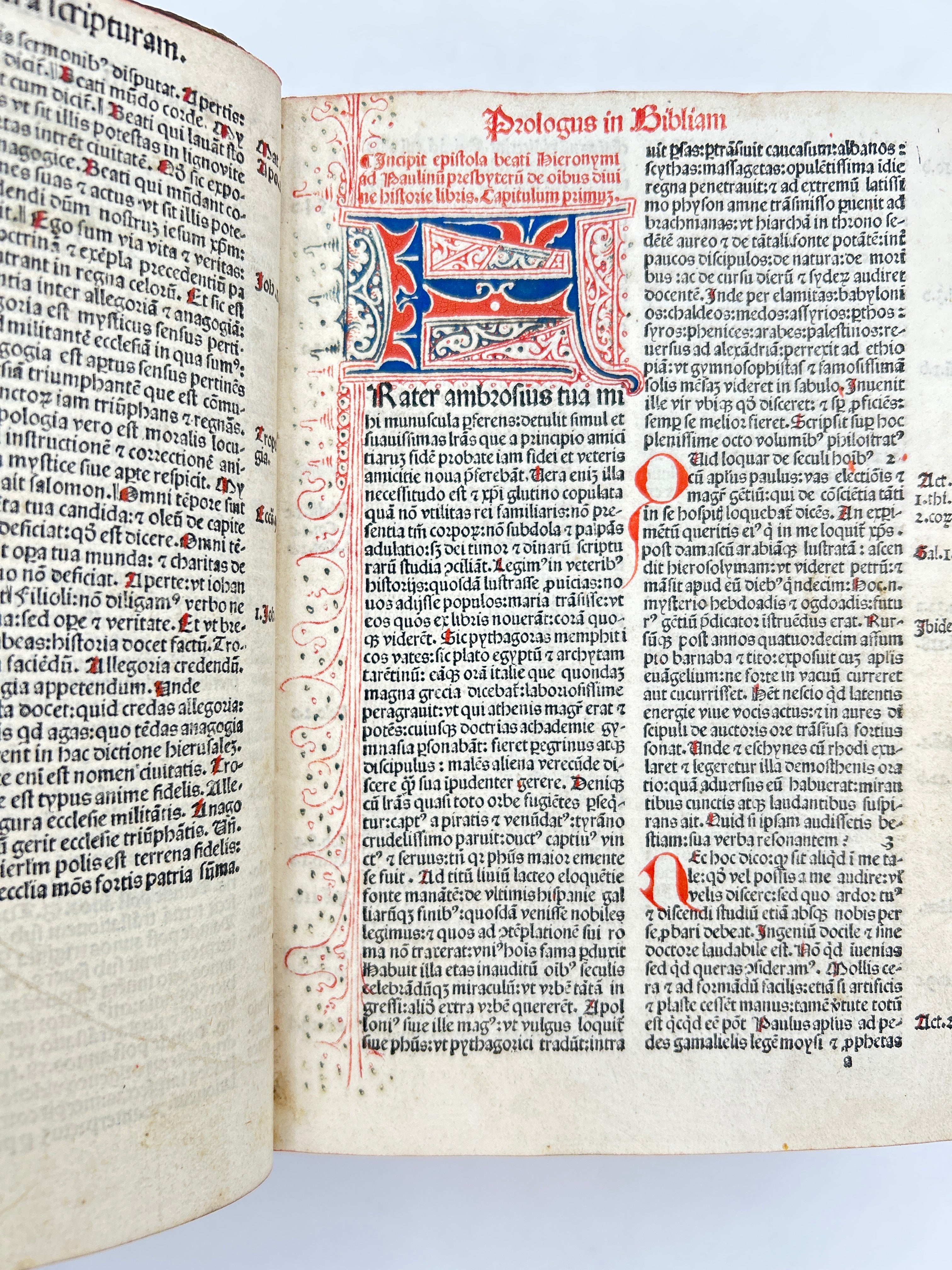

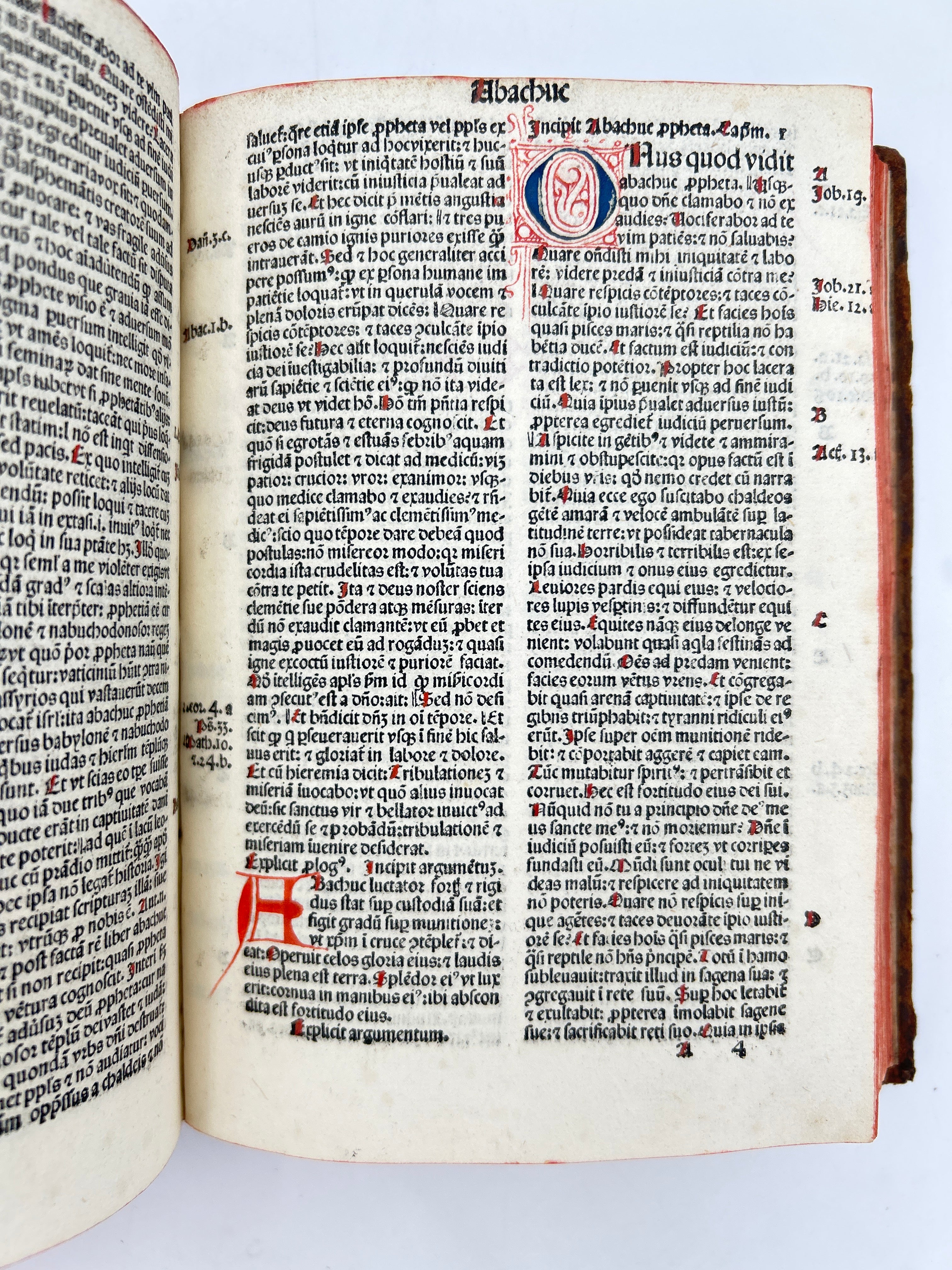

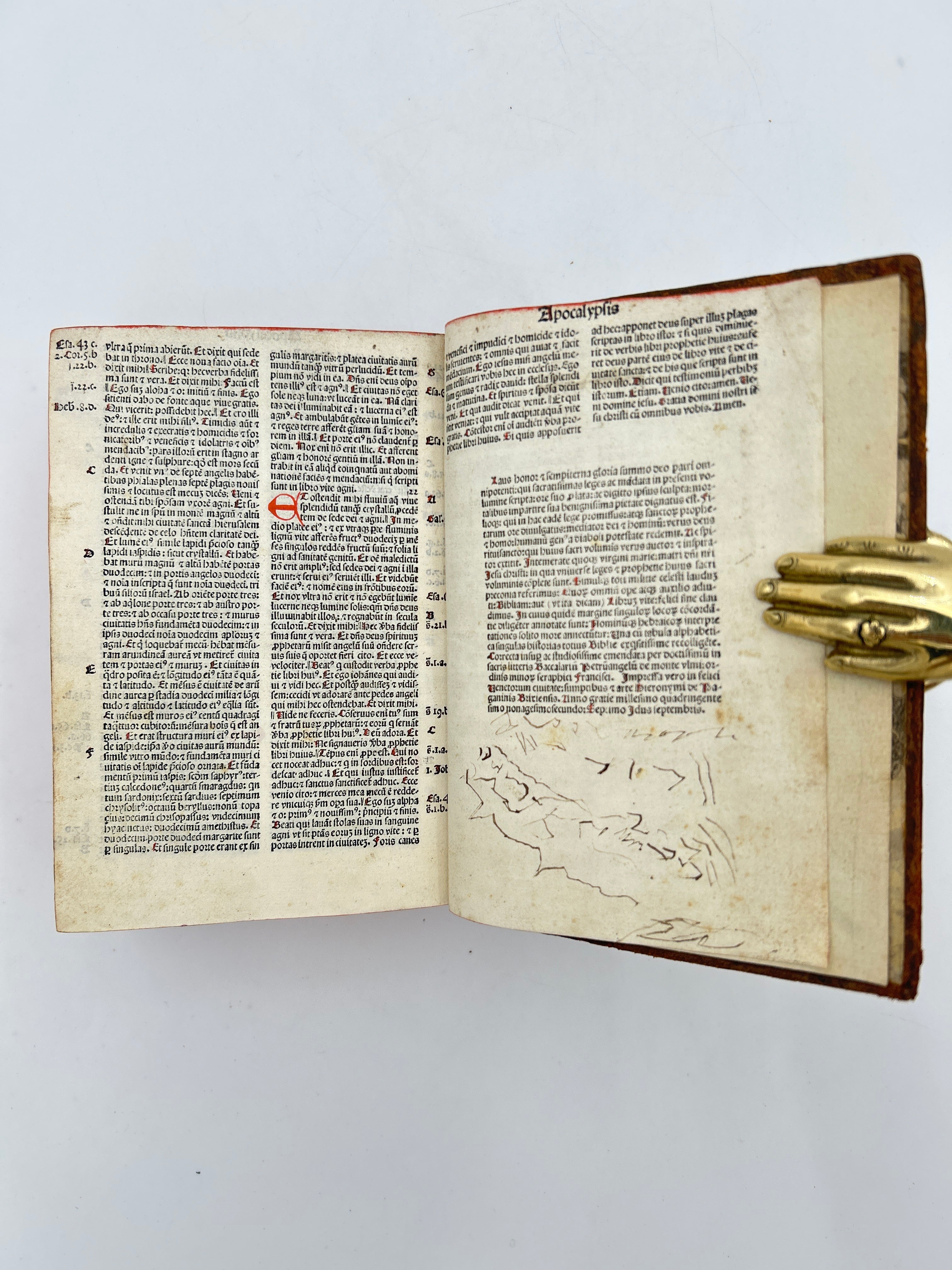

With the advent of movable type printing in the mid-15th century, most famously through Johannes Gutenberg’s printing of the Bible around 1455, the production of Bibles shifted dramatically. Gutenberg’s Bible, printed in Latin (the Vulgate), combined mechanical innovation with traditional aesthetics. He deliberately designed it to mimic the look of a handwritten manuscript, using a blackletter typeface that resembled the Gothic script common in handwritten Bibles. To enhance the appearance, spaces were left for hand-illuminated initials, rubrics (red text), and decorative elements, which were added later by hand—blurring the line between manuscript and print.

For several decades after the press was introduced, printers often continued this hybrid approach. Early printed Bibles (known as incunabula, or books printed before 1501) frequently included hand-finished flourishes, marginal notes, and even decorative initials painted by artists or scribes, giving them the familiar richness of the older manuscript tradition. This practice gradually faded as printing became more standardized and efficient, but it marked a fascinating transitional moment when two worlds—manual craftsmanship and mass production—briefly coexisted. This period laid the foundation for the wide dissemination of Scripture and, ultimately, the religious and cultural transformations of the Reformation and beyond.

Description

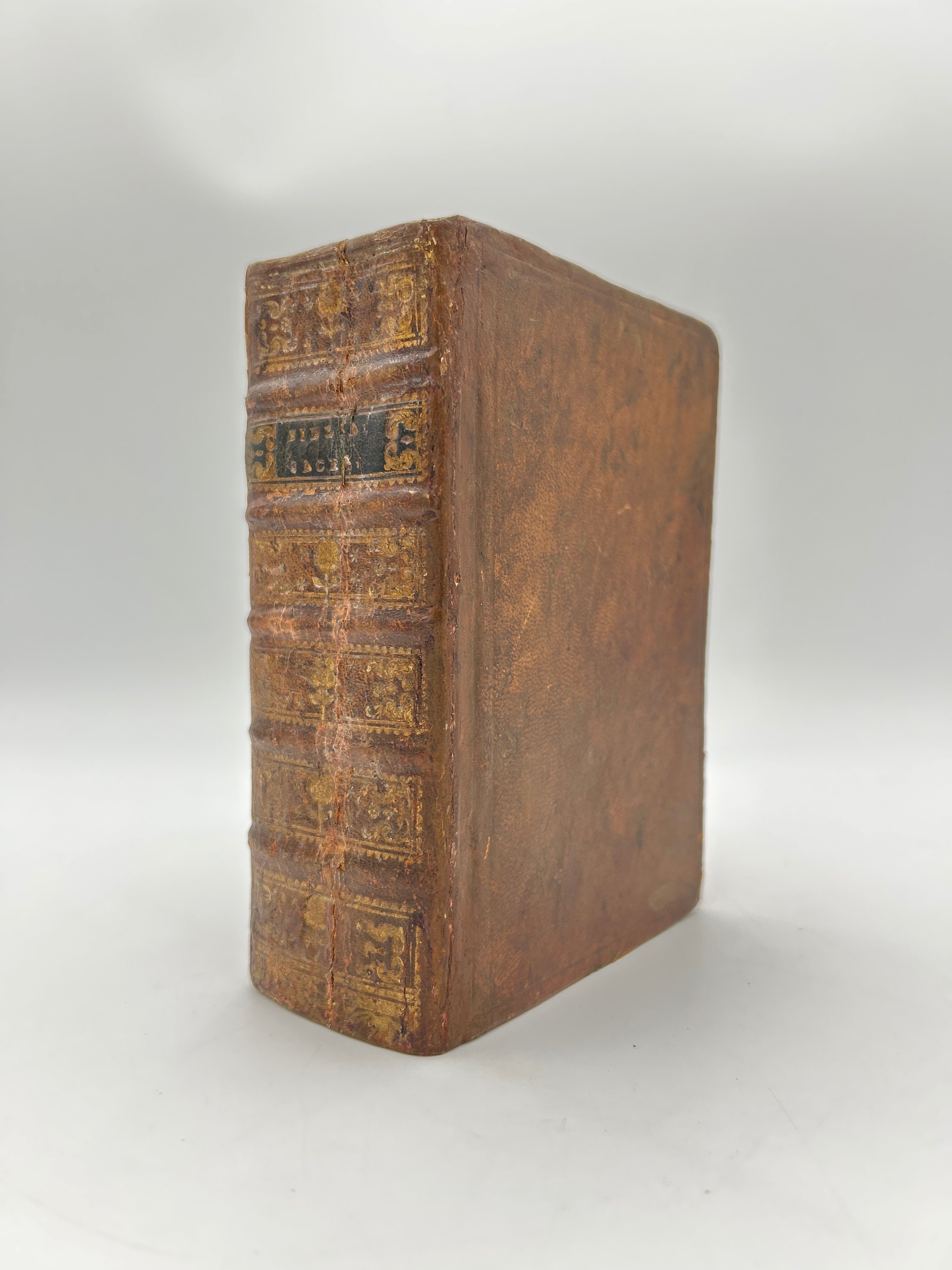

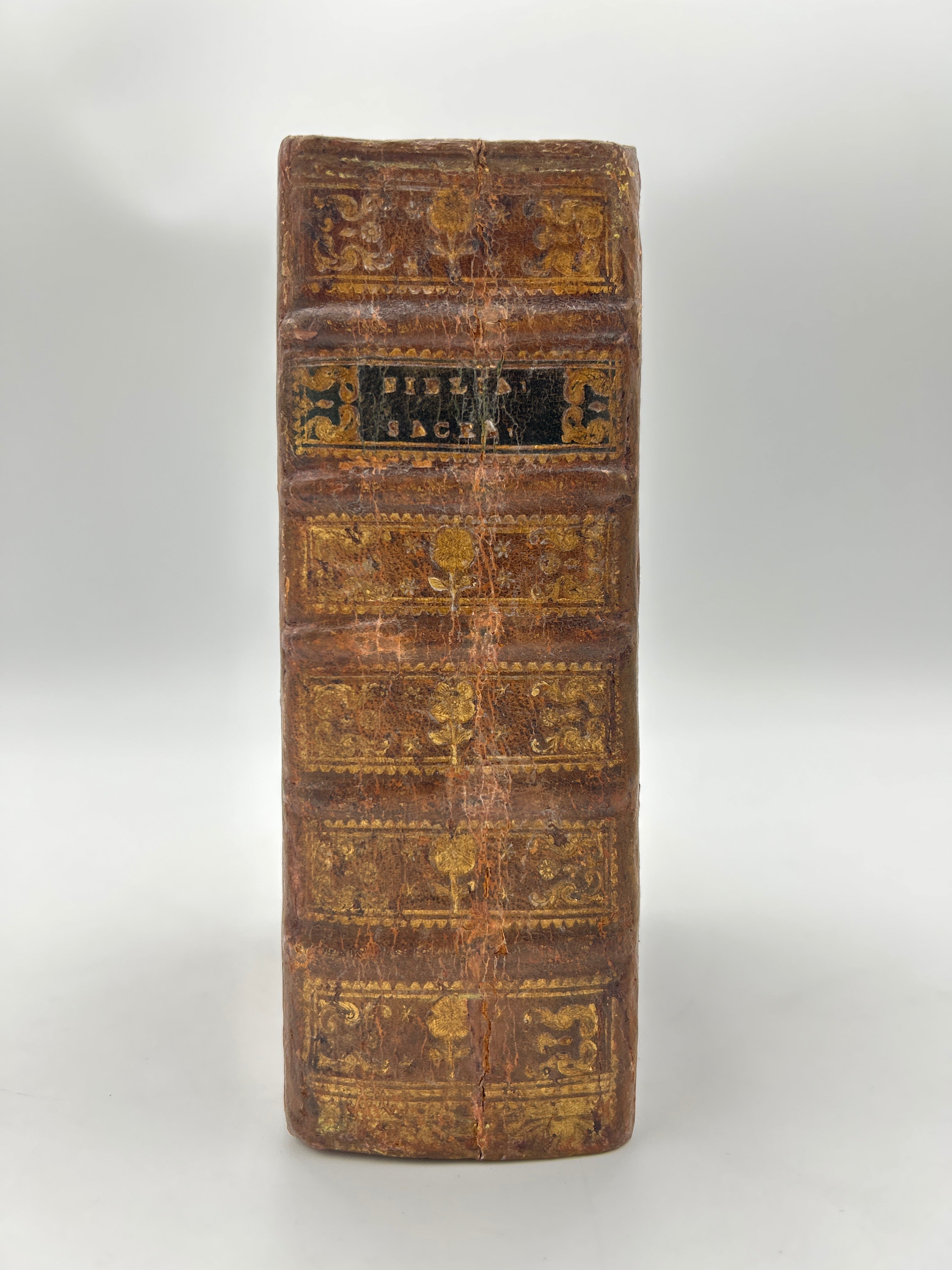

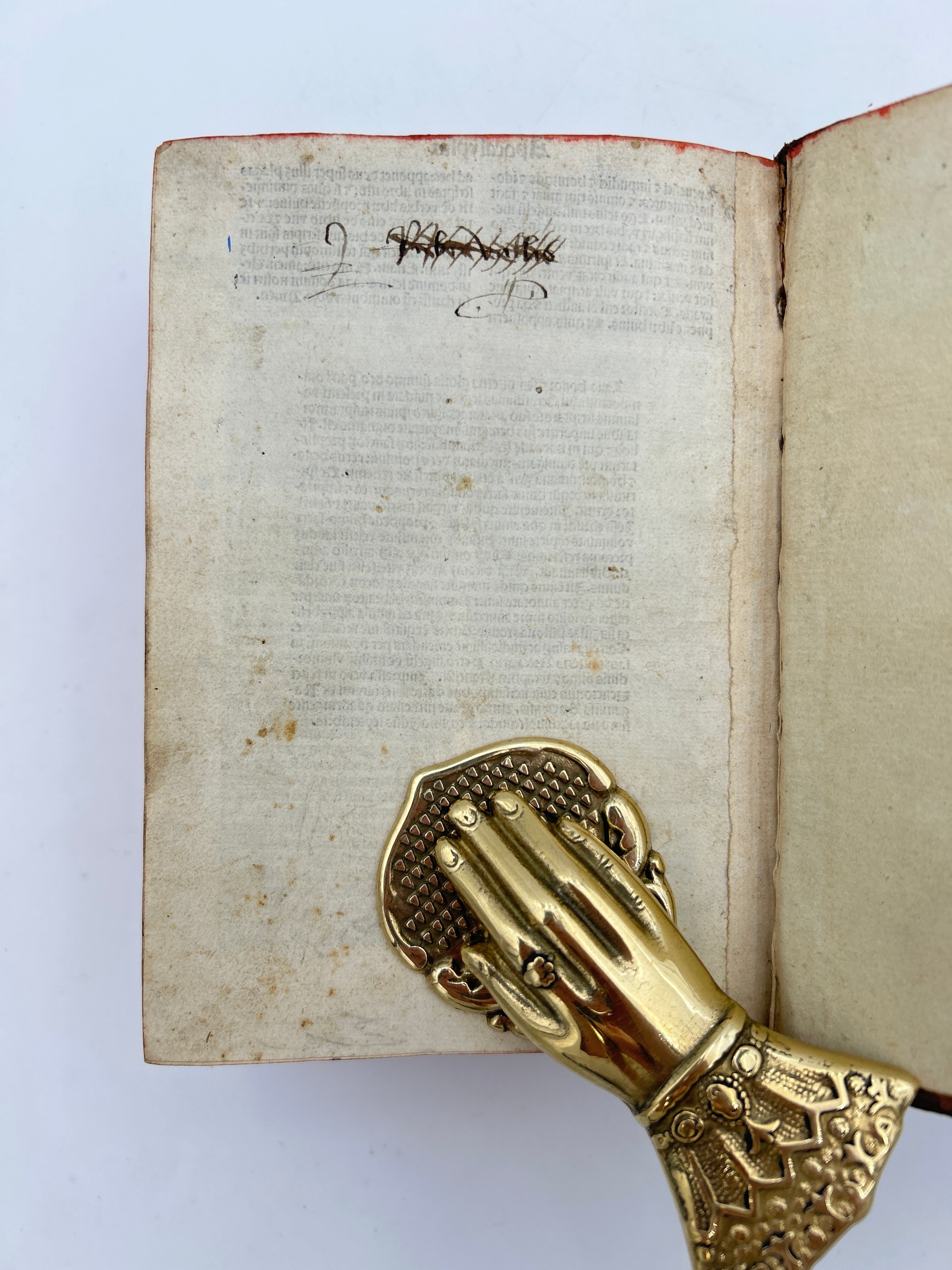

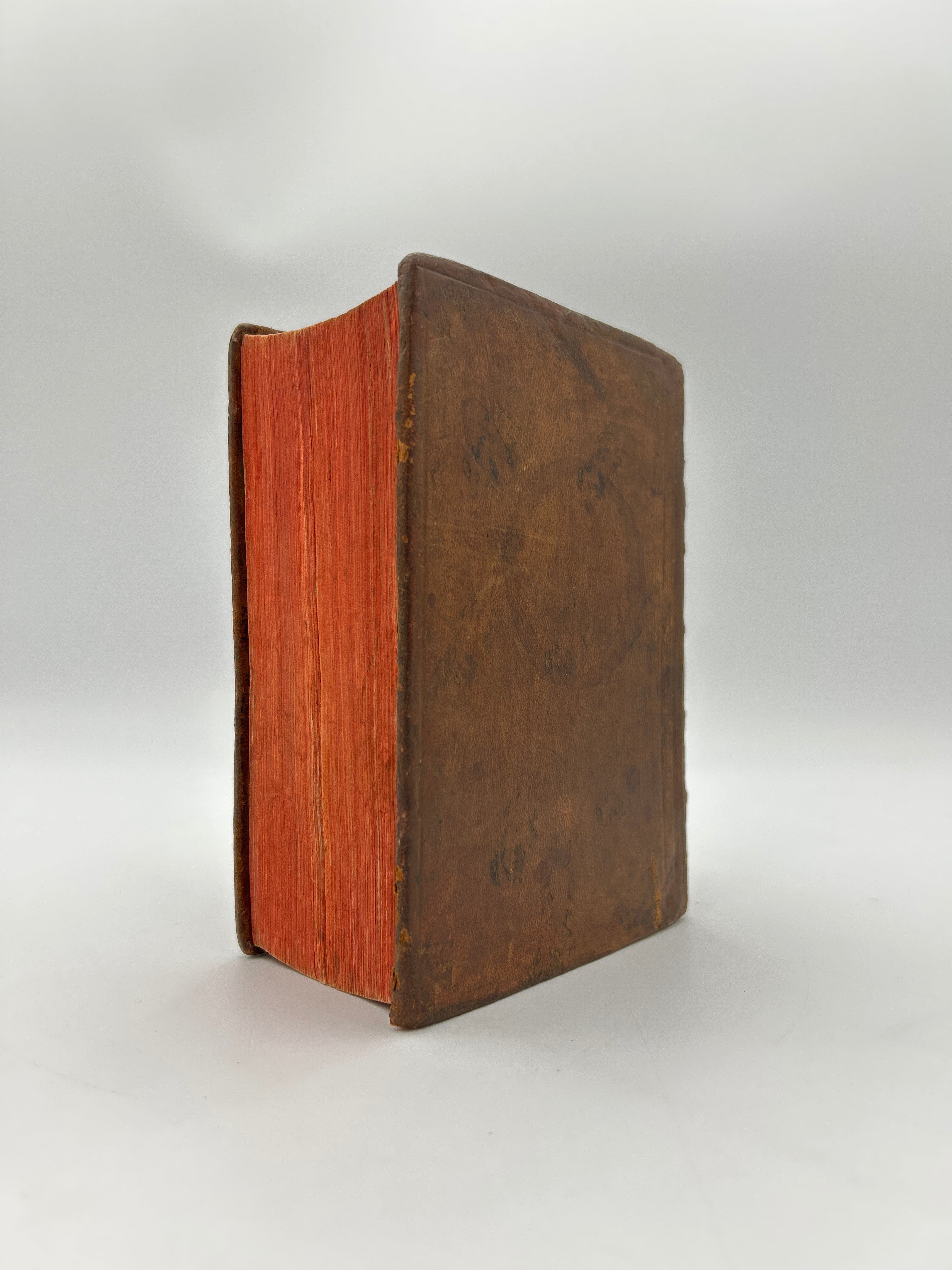

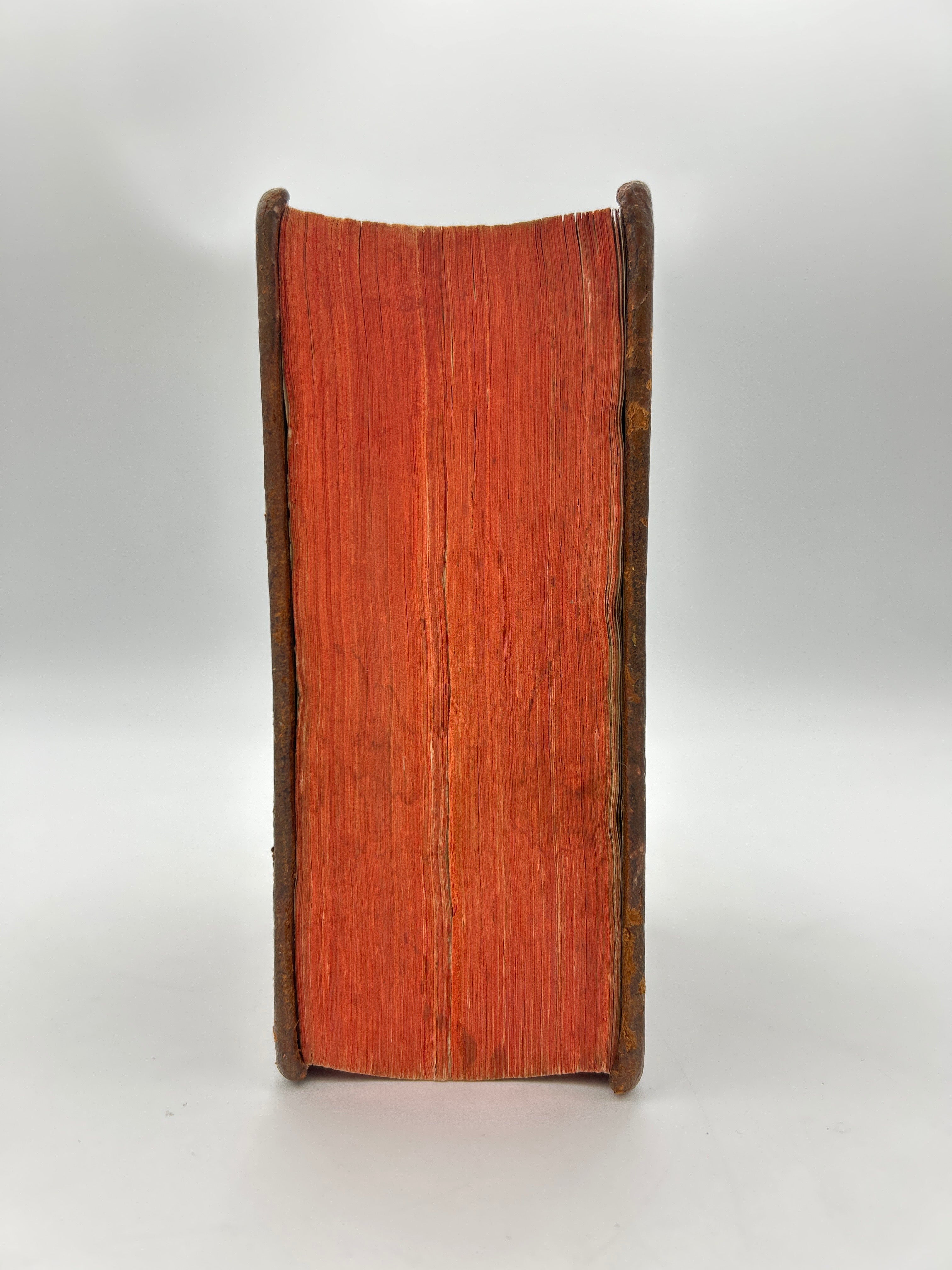

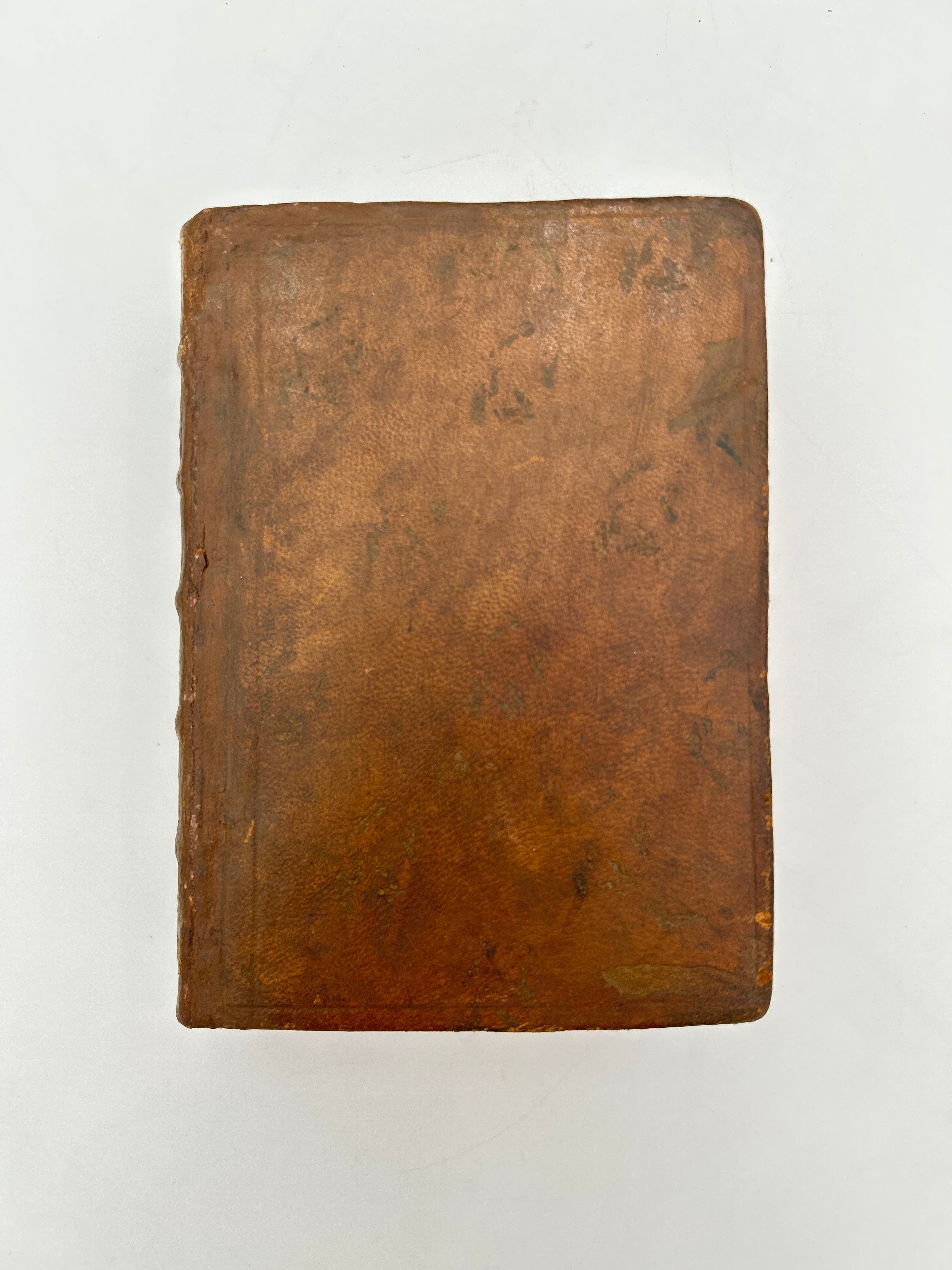

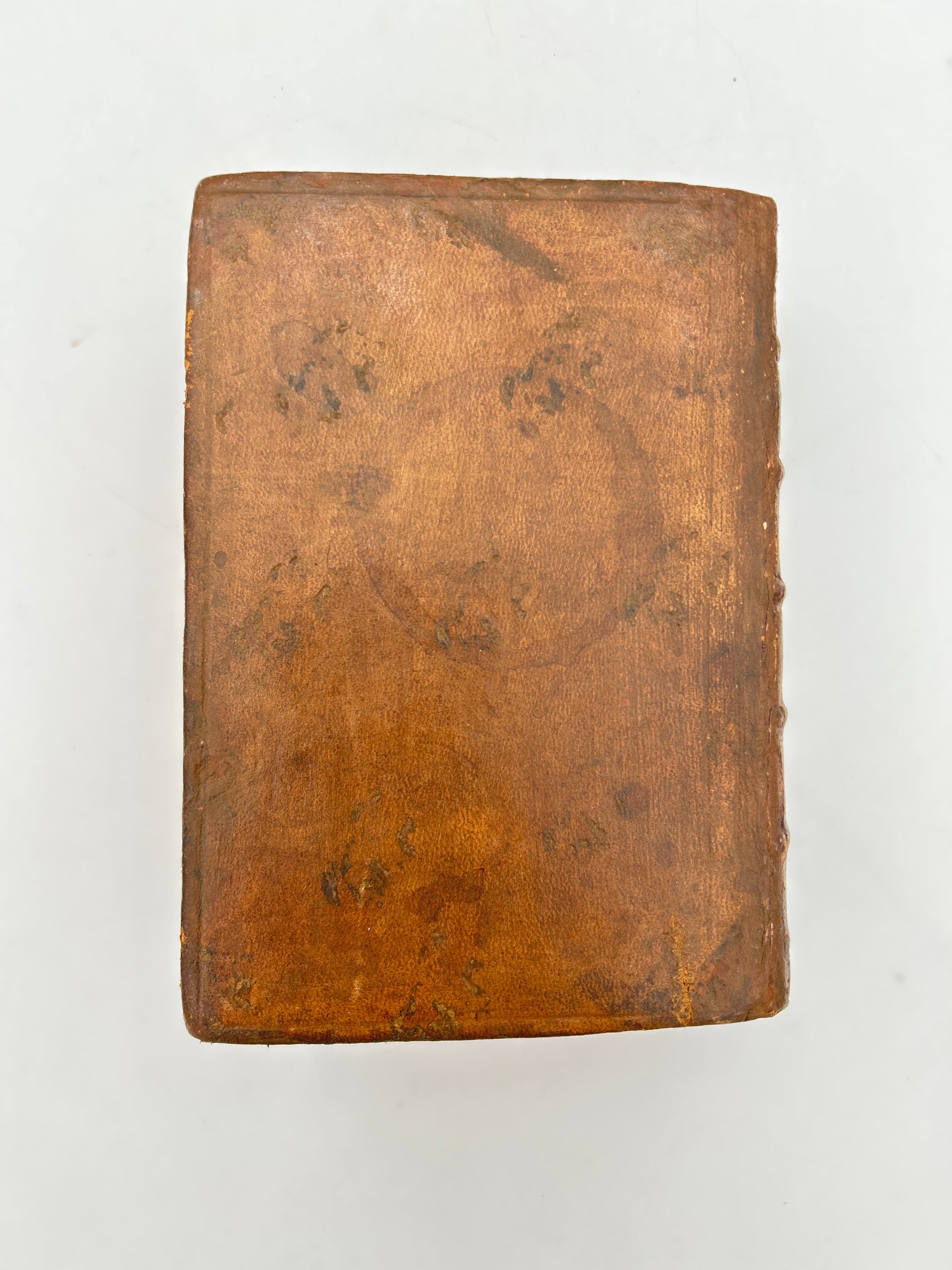

Later rebinding. Brown leather binding with five raised bands on spine. Gilt embossed detailing in each compartment with a black leather label in the second compartment with gilt lettering. All edges red. Woodcut image on preliminary page. All black letters type set with all red and blue ink added in by hand.

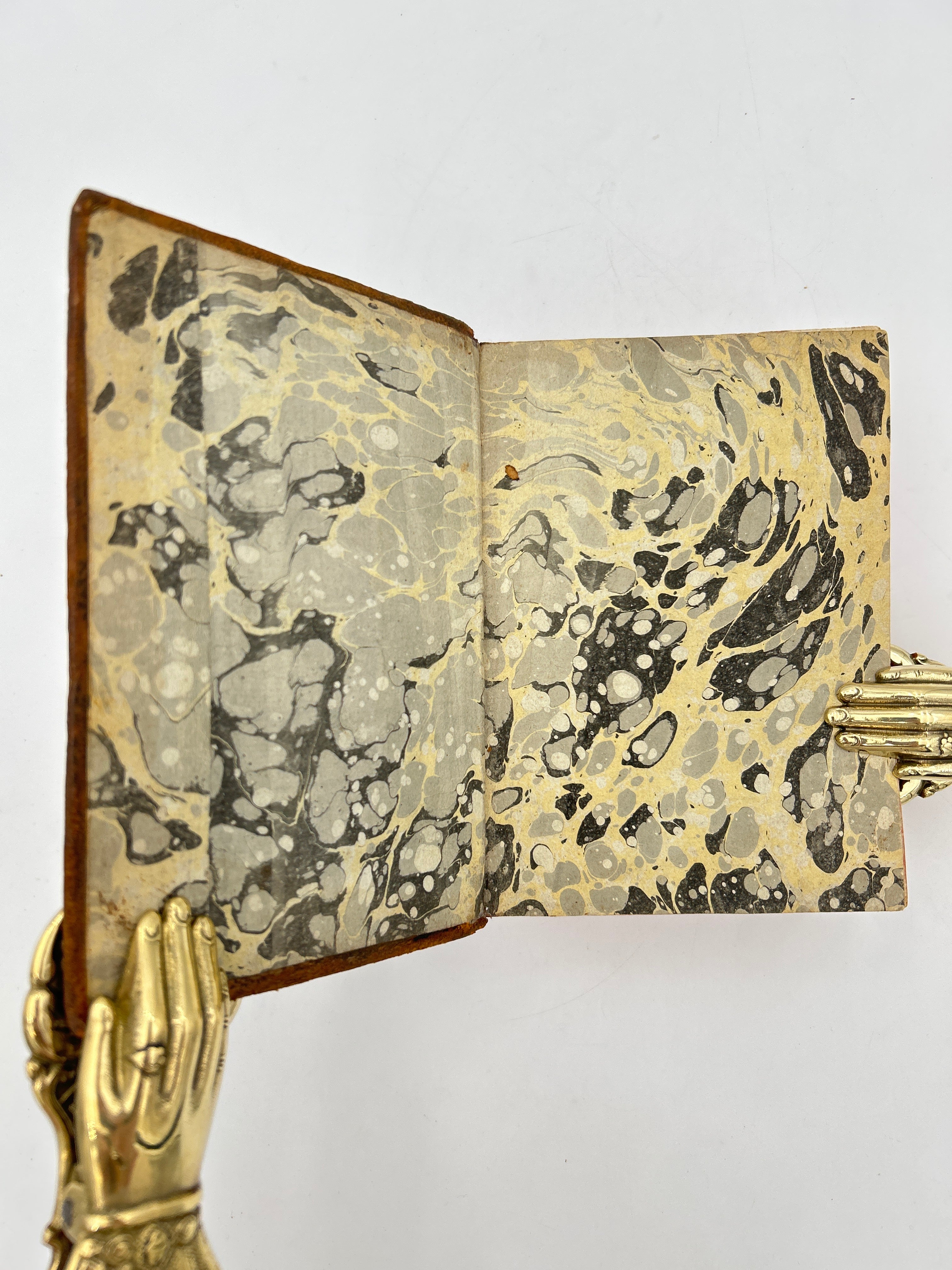

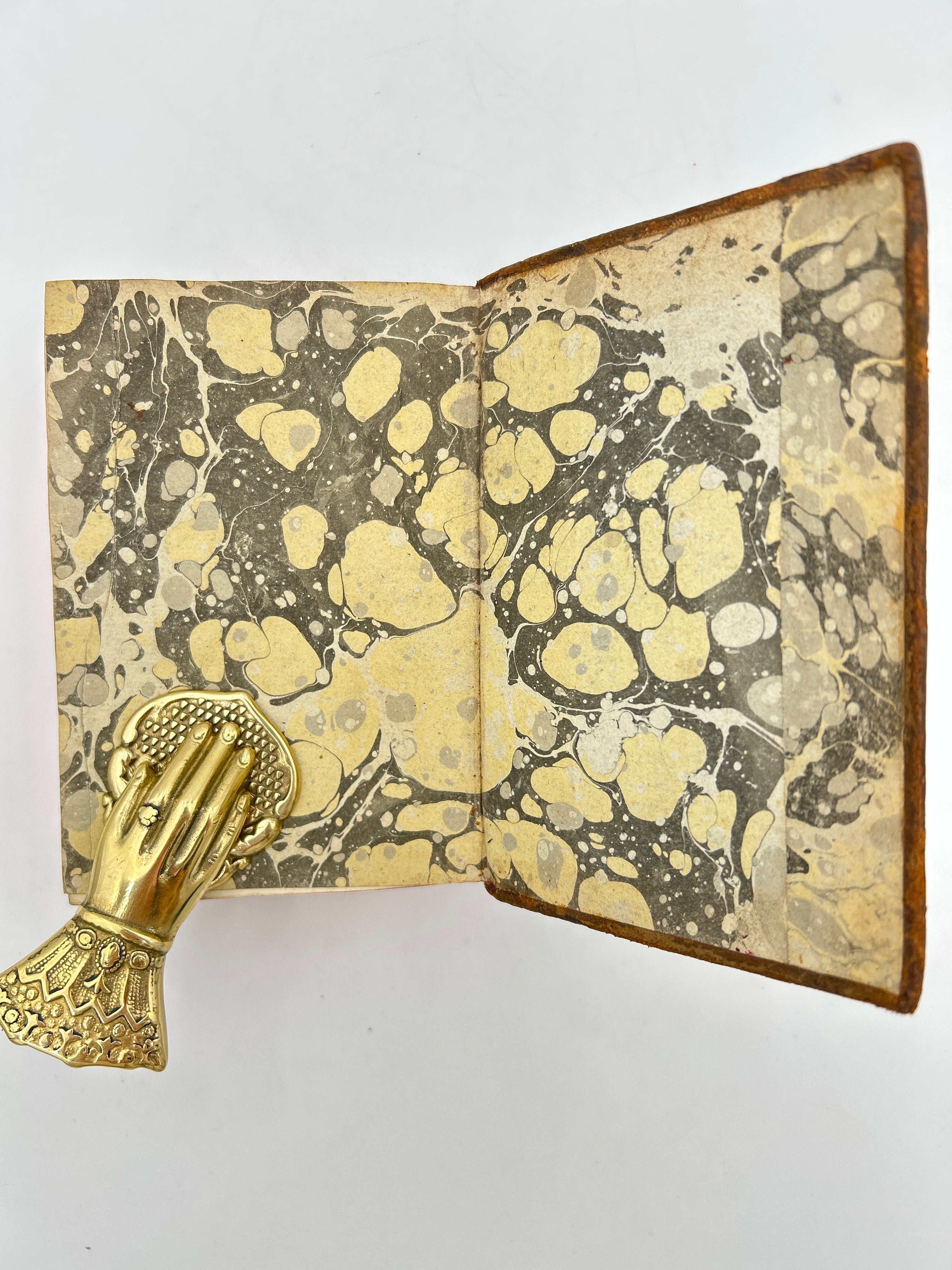

General discoloration to boards. All points bumped. Very little rubbing to the binding. Creasing to the spine. Few pages with slight chipping to the edges. Preliminary title page with blue mark to Saint Peter’s shoulder and two sections of handwriting surrounding the image. Final page with ink marking in lower margin and to blank opposite side. Marbled endpapers. Slight fading of the red on lower right corner of fore-edge. Book worm marks to lower board. Ring shape impression to lower board. Break halfway through lower spine. No pages lost. Fully intact. Fine condition.