The printing history of the Bible began in the mid-15th century with Johannes Gutenberg’s Latin Bible (c. 1454–1455), the first major book printed using movable type in Europe, which marked a turning point in both religious life and the spread of knowledge. Over the following centuries, Bible printing expanded rapidly, aided by the Reformation, which emphasized access to scripture in vernacular languages; this led to translations and printings in German, English, French, and many other languages. Printers gradually improved accuracy, layout, chapter and verse numbering, and cross-references, while advances in typography and paper made Bibles more affordable and widely available, transforming the Bible from a manuscript tradition accessible mainly to clergy into a book owned and read by ordinary people.

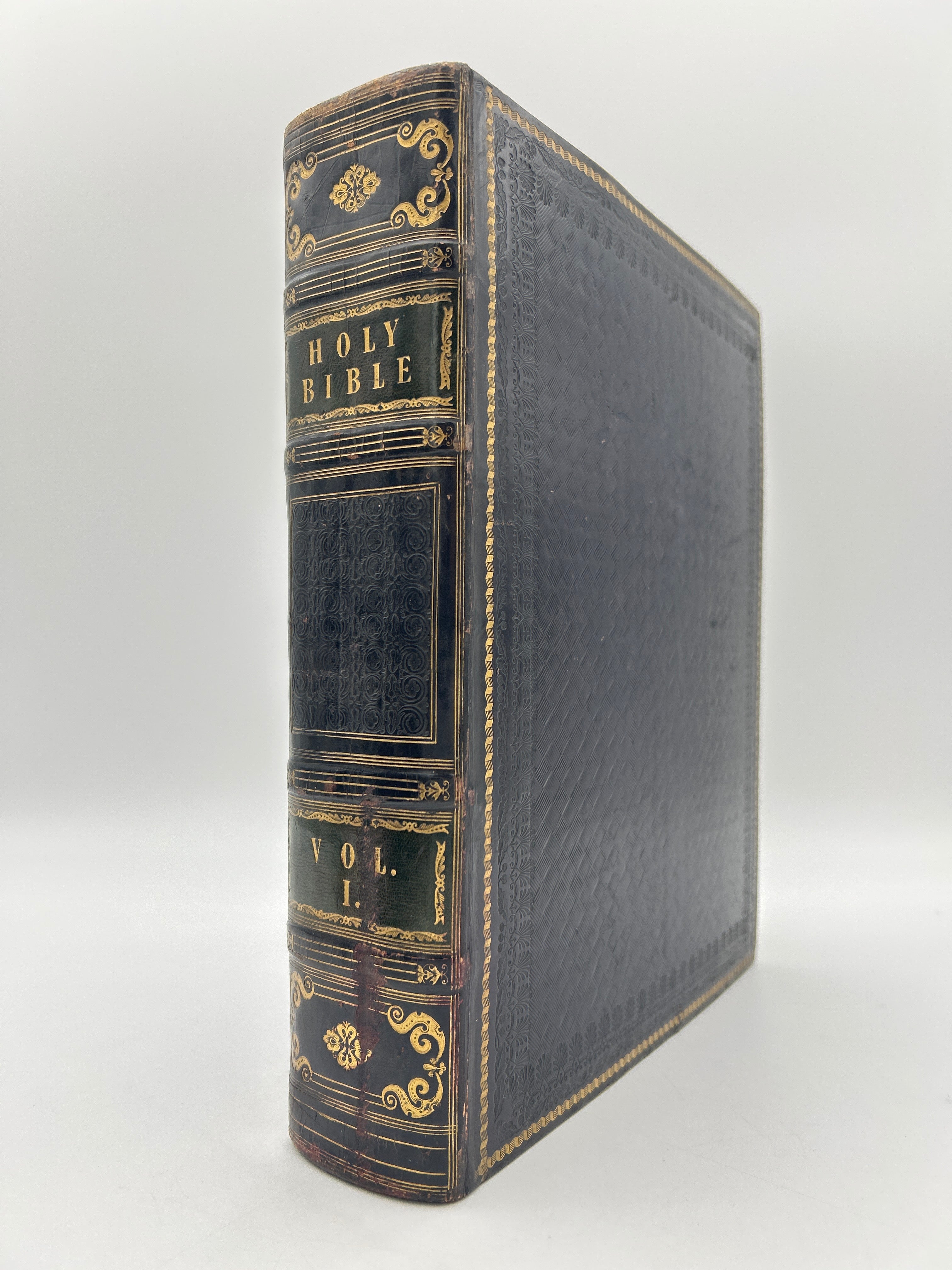

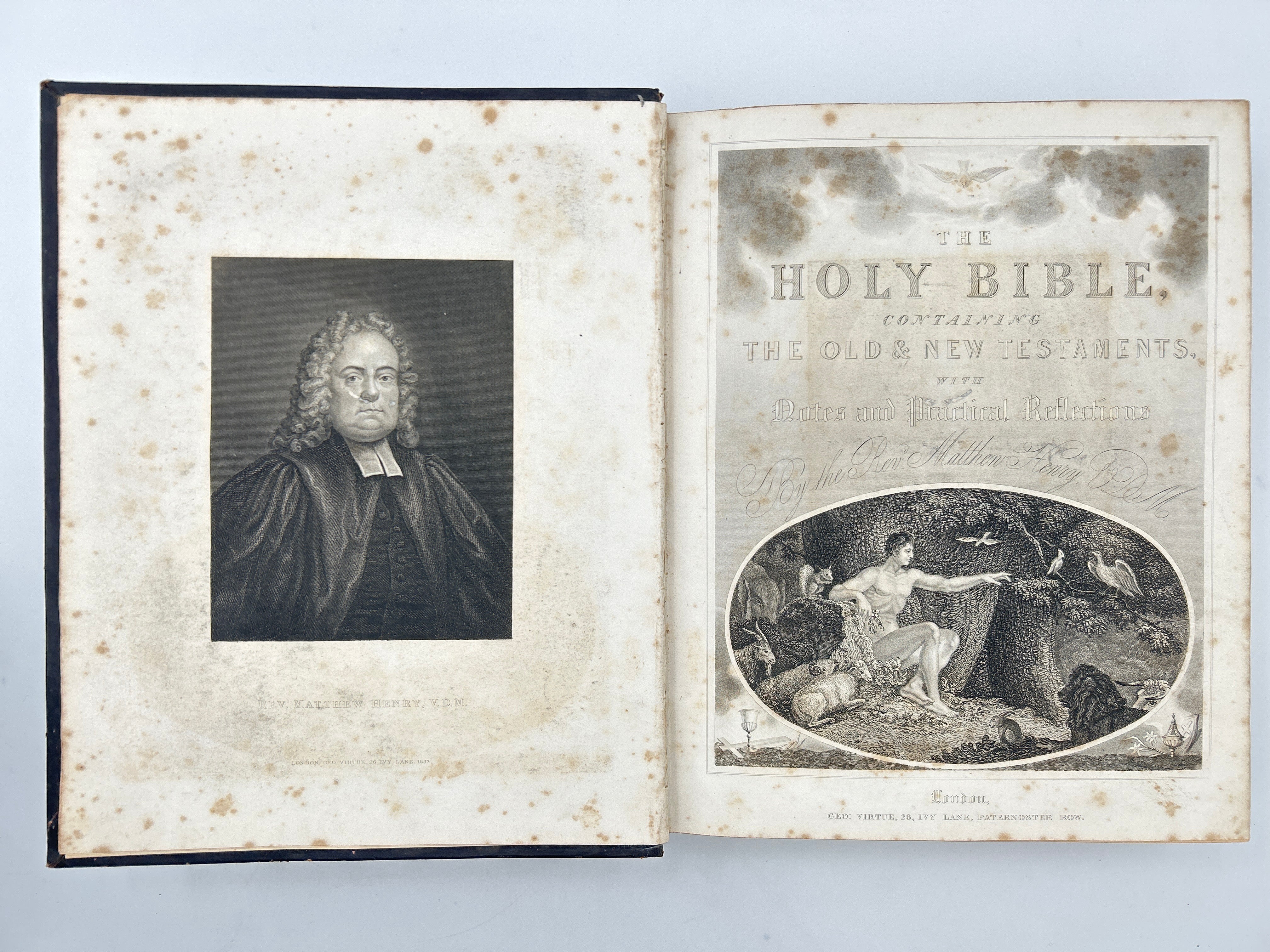

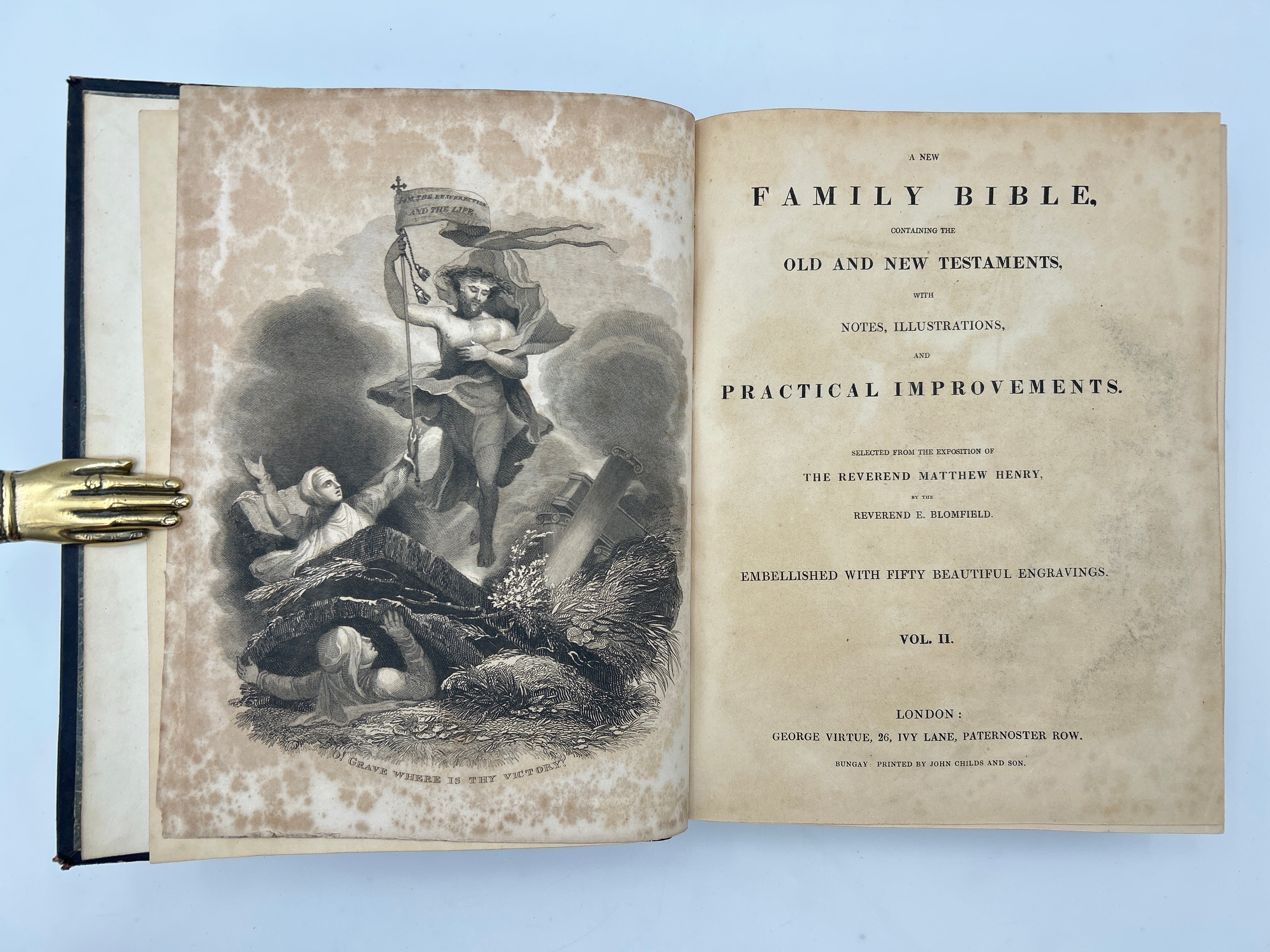

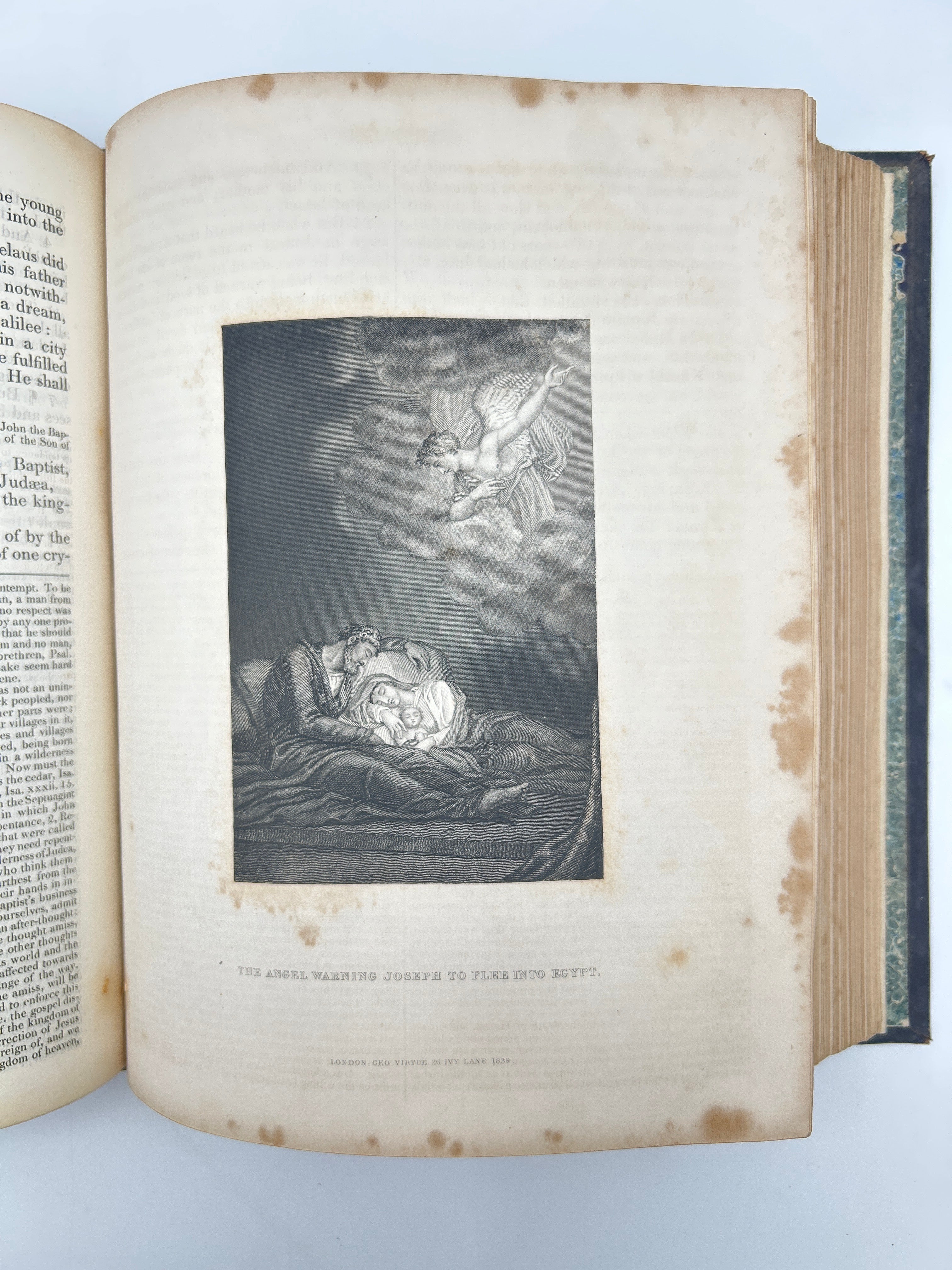

In the 1800s, many Bible editions were printed in multiple volumes, reflecting both scholarly ambition and the aesthetics of book production in the 19th century. Large, multi-volume sets often separated the Old and New Testaments or divided scripture alongside extensive commentaries, concordances, maps, and critical notes, appealing to clergy, scholars, and wealthy households. This period also saw the influence of modern biblical scholarship and archaeology, leading publishers to produce expansive, carefully edited multi-volume works that treated the Bible not only as sacred scripture but also as a historical and literary text.